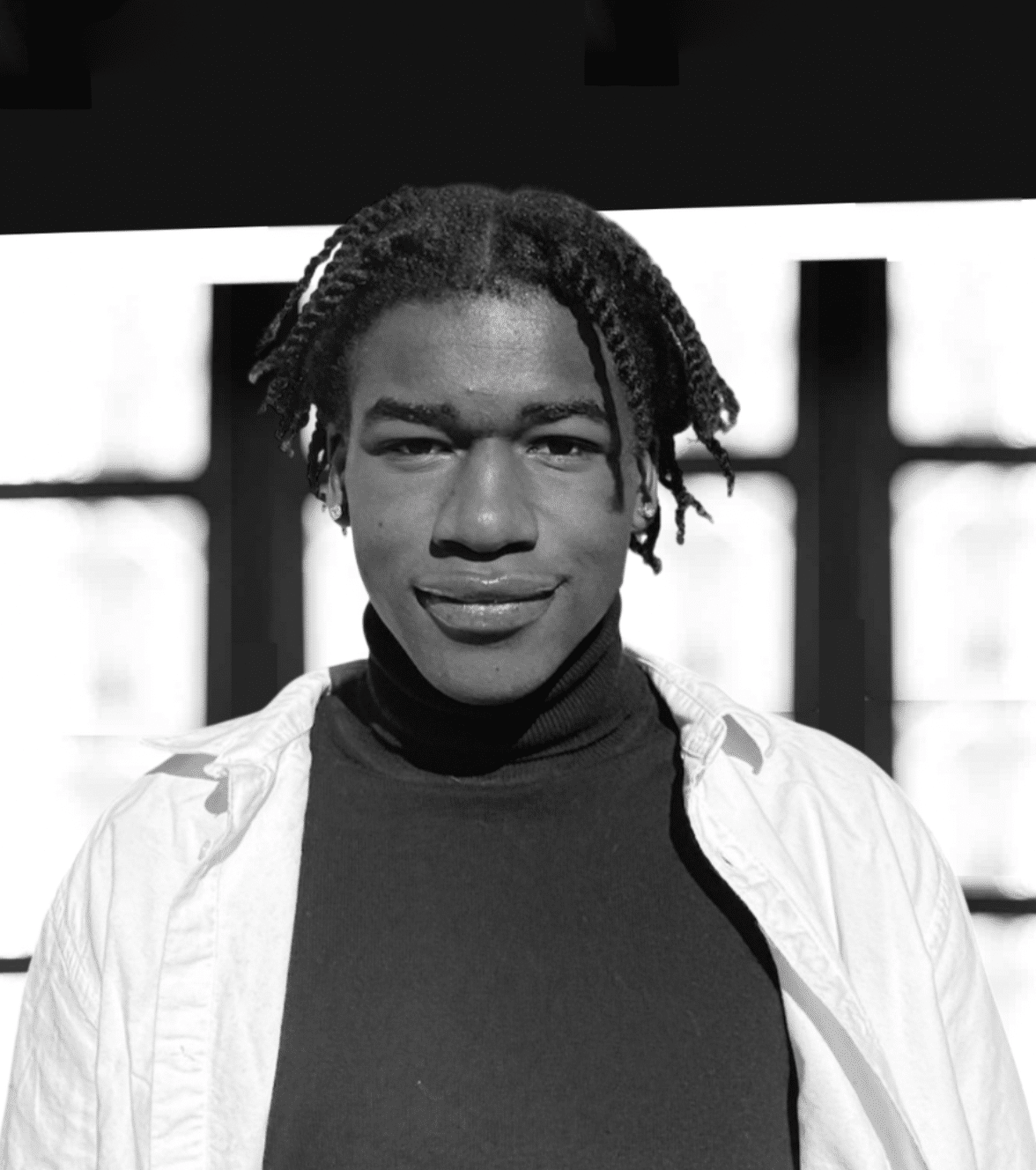

Silvia MERLER Affiliate Fellow at Bruegel (Brussels) Html code here! Replace this with any non empty text and that's it. The recent months have been dense with events for the Italian banking system, which saw several episode of resolution in 2015, and the setup of a guarantee scheme on non-performing loans and of a bank-financed backstop fund, in early 2016 (Merler 2016a 2016b). These three episodes are strictly connected and they have as a common denominator the unresolved issues in the Italian banking system. Italian banks have been very resilient to the first wave of financial crisis in 2008, due to their low exposure to US subprime products and to the fact that Italy did not have a pre-crisis housing bubble. However, when the global financial crisis turned into a euro sovereign banking crisis in 2010, things started to deteriorate for the sector. Italian banks were among the worst performers

Ce contenu est réservé aux abonné(e)s. Vous souhaitez vous abonner ? Merci de cliquer sur le lien ci-après -> S'abonner