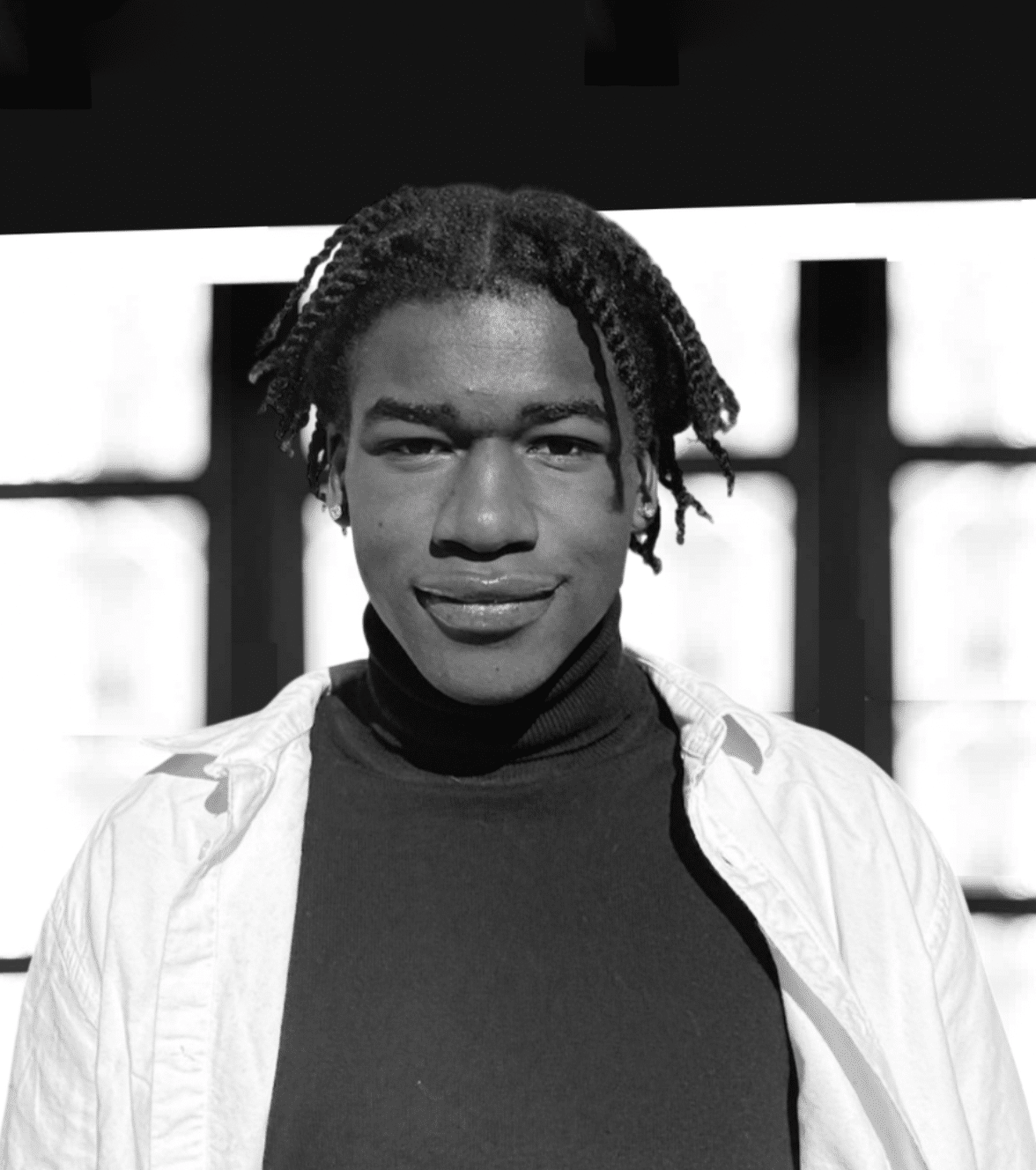

Paweł ZERKA Economist and political scientist, head of foreign policy and international relations research program in WiseEuropa institute, a Warsaw-based think-tank (www.wise-europa.eu) Poland belongs to those European countries that run the risk of losing the most as a result of the British referendum and the following consolidation of the EU’s hard core. Ironically, the national right government of Law and Justice (PiS) seems to be relatively optimistic about what it entails. On a number of occasions, its representatives have suggested that Brexit confirms their earlier conviction about the EU’s deep crisis and that it may open the door for a major European reform which, in their view, should consist in the EU’s comeback to the roots. Before the UK referendum, Warsaw could reasonably expect that Britain would serve as its valuable ally in seeking an EU of variable geometries, with a stronger role of national capitals and a greater emphasis

Ce contenu est réservé aux abonné(e)s. Vous souhaitez vous abonner ? Merci de cliquer sur le lien ci-après -> S'abonner