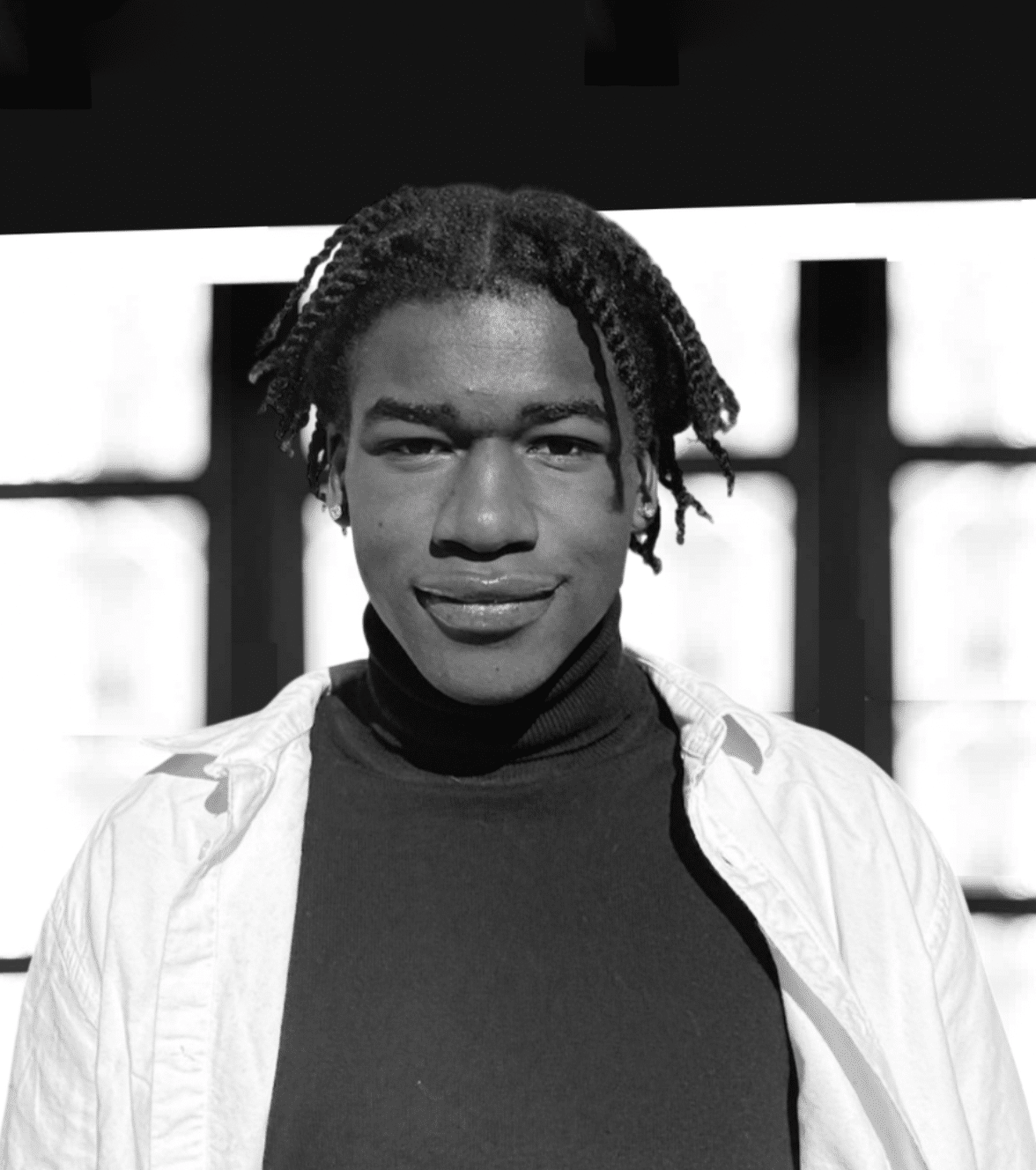

Erik Brattberg Director of the Europe Program and a Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, DC The Covid-19 pandemic is challenging international cooperation. This is notably the case of the already damaged relationship between the EU and the United States, since Donald Trump halted travels from Europe to US on March 11. Is the coronavirus crisis going to durably dash an already overstretched transatlantic link ? Read senior analyst Erik Brattberg’s insights. Having already deteriorated significantly since President Donald Trump assumed office in 2017, the transatlantic relationship is now at risk of being further weakened during the coronavirus. Rather than serving as an impetus to restore the battered relationship between Washington and European capitals, the presence of the global pandemic is accelerating already existing negative transatlantic trends. If Trump is reelected in November, he will likely continue to double down on his “America First” foreign policy, skepticism

Ce contenu est réservé aux abonné(e)s. Vous souhaitez vous abonner ? Merci de cliquer sur le lien ci-après -> S'abonner