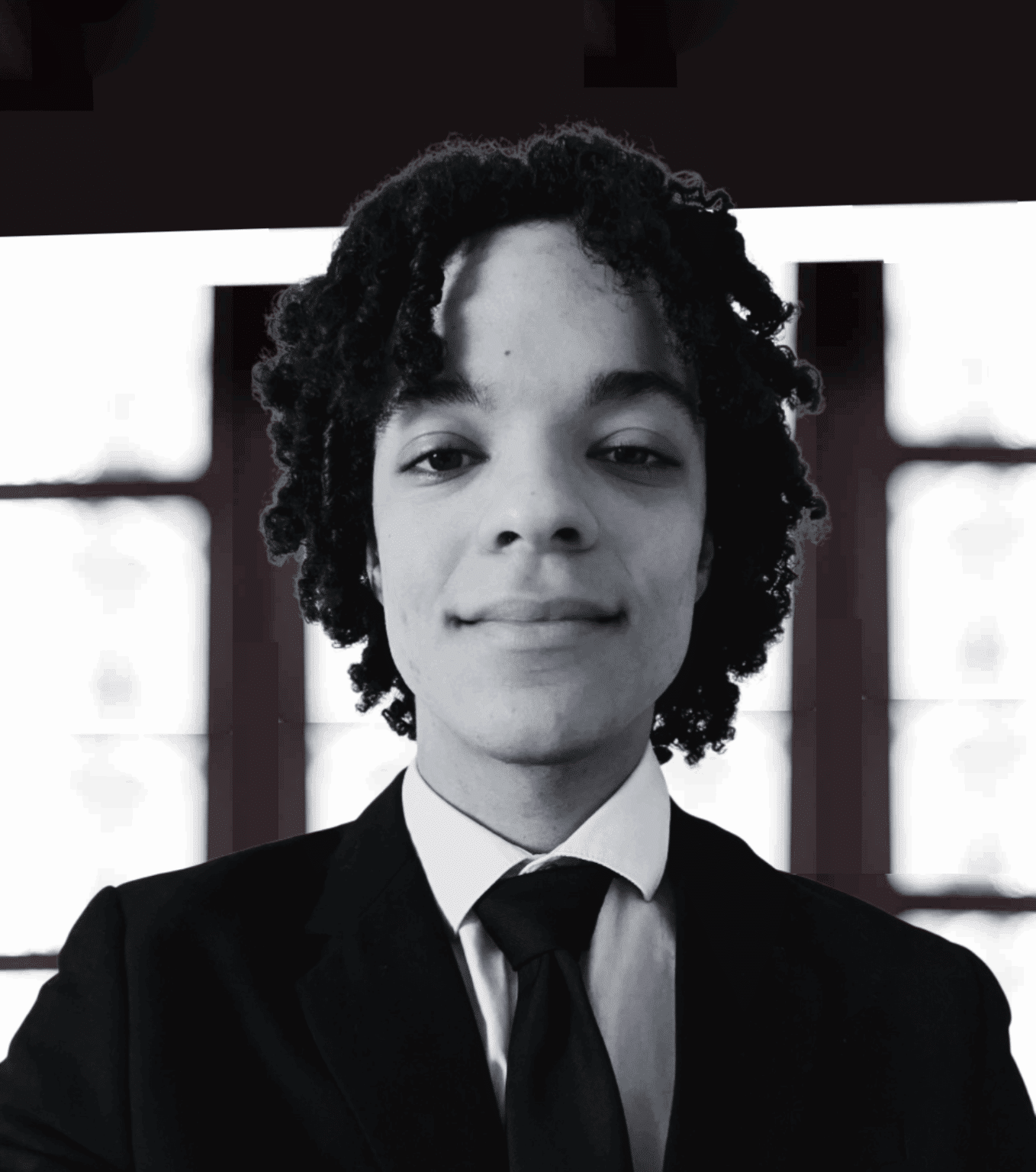

Claude FISCHER

Director, ASCPE – Les Entretiens européens

Html code here! Replace this with any non empty text and that's it.

By comparing the Energy union to the ECSC, the Commission has voiced aspirations that fit with our own proposals[1]. But the objectives of the new project need to be discussed, especially since there is no global vision to give it coherence. The ECSC had a strategy of industrial expansion. Today, too much emphasis is placed on demand reduction policies alone, disregarding the fact that the European Union also needs a supply-side policy to stimulate new growth and boost its global competitiveness.

In today’s context of crisis and rising tension with producing countries – especially Russia – energy security has (once again) become a vital economic pillar. To reduce imports (currently 53% of our consumption) and our annual €400 billion energy bill (before the drop in oil prices), the Commission has proposed that we further diversify energy sources and supply routes, develop electricity exchanges between the Member States and negotiate intergovernmental agreements with third countries. Rather than putting “an end to our dependence”, shouldn’t we try to manage complex interdependencies with energy producers and distributors more efficiently, bearing in mind that most of them live off the associated economic rent? How can we increase our exports and build new trade relations with these countries, which need to diversify their economies, and thereby promote our own industries?

The Commission has suggested building an interconnected energy market to enable each Member State to export 10% of its electricity production to its neighbours. It says that, as a result, consumers would save €12 to 40 billion annually, but meeting the 10% electricity interconnection target would require an investment of €40 billion. We cannot however ignore the fact that some Member States are far from producing enough electricity to meet their own needs and that the fragmentation of the internal market, coupled with the boosting of renewable energy, has had counter-productive effects: higher prices and grid costs and a greater dependence on coal to the detriment of gas and nuclear power, not to mention the fact that the business models of the big energy firms have been damaged and that fuel poverty is on the rise. Wouldn’t it be wiser to think about the incentives needed to achieve a much better price investment ratio?

Such a strategy requires an energy solidarity pact, with the aim of developing an integrated market that optimises diversified, carbon-free electricity production at least cost. Although the 3×20 strategy had the effect of dividing Europeans instead of promoting solidarity, the Commission is persisting along the same lines despite growing criticism: it is imposing 3 restrictive new targets, which interact and oppose any desire to promote national energy diversity and do not give the Member States any real choice regarding their energy mix. Furthermore, although energy efficiency is a vital issue, all initiatives to promote it to date have failed because they have not developed into a real industrial policy that would not only reduce consumption but also improve energy performance in the residential and transport sectors.

Lastly, the 2030 greenhouse gas reduction target of 40% (60% by 2050) is justified but it must be brought into line with our growth model and our global competitiveness. Any reform of the carbon quota market must be accompanied by the introduction of an appropriate tax system and (why not) the establishment of a central carbon bank. Only by clarifying the economic stakes can we bring on board countries like China and the USA, which have become the biggest polluters on the planet. They could then become our allies in promoting carbon-free energy sources.

[1] See the booklet published by Confrontations Europe “Energy: a pioneer of European construction yesterday, a driver of European reconstruction today. For a competitive and inclusive European climate strategy by 2030.” May 2013. www.confrontations.org.

Nuclear power at the centre of a fierce battle on competitiveness and climate

The share of nuclear power in the European energy mix has dropped by 4.9% since 2002, from 32% to 26.7%. Bearing in mind that the global nuclear industry is taking off again – with the construction of 72 new reactors worldwide (vs. 25 in 2004) – a European disengagement now would be detrimental not only in terms of exports but also in terms of safety, which is a global public good.

Yet the nuclear industry needs long-term contracts that require the Commission’s approval. After Mankala in Finland and Exeltium in France, the Commission has approved the British energy market reform, notably the CfD (Contract for Difference). This sends a strong message to countries like Poland, which are reflecting on the possible role of nuclear power in their energy mix alongside coal.

The Commission’s decision has been challenged by Austria and Germany, which are threatening to bring the matter before the Court of Justice, thus provoking a reaction from 8 countries[1]. In an open letter to the Commission, they have demanded that nuclear power be recognised as a source of carbon-free energy.

The role of nuclear power in the European energy mix is still a controversial subject among the Member States: some want to step up cooperation in the field while others are battling to prevent it. Meanwhile, the IPCC has announced that without nuclear power global warming reduction targets will not be met.

Claude FISCHER