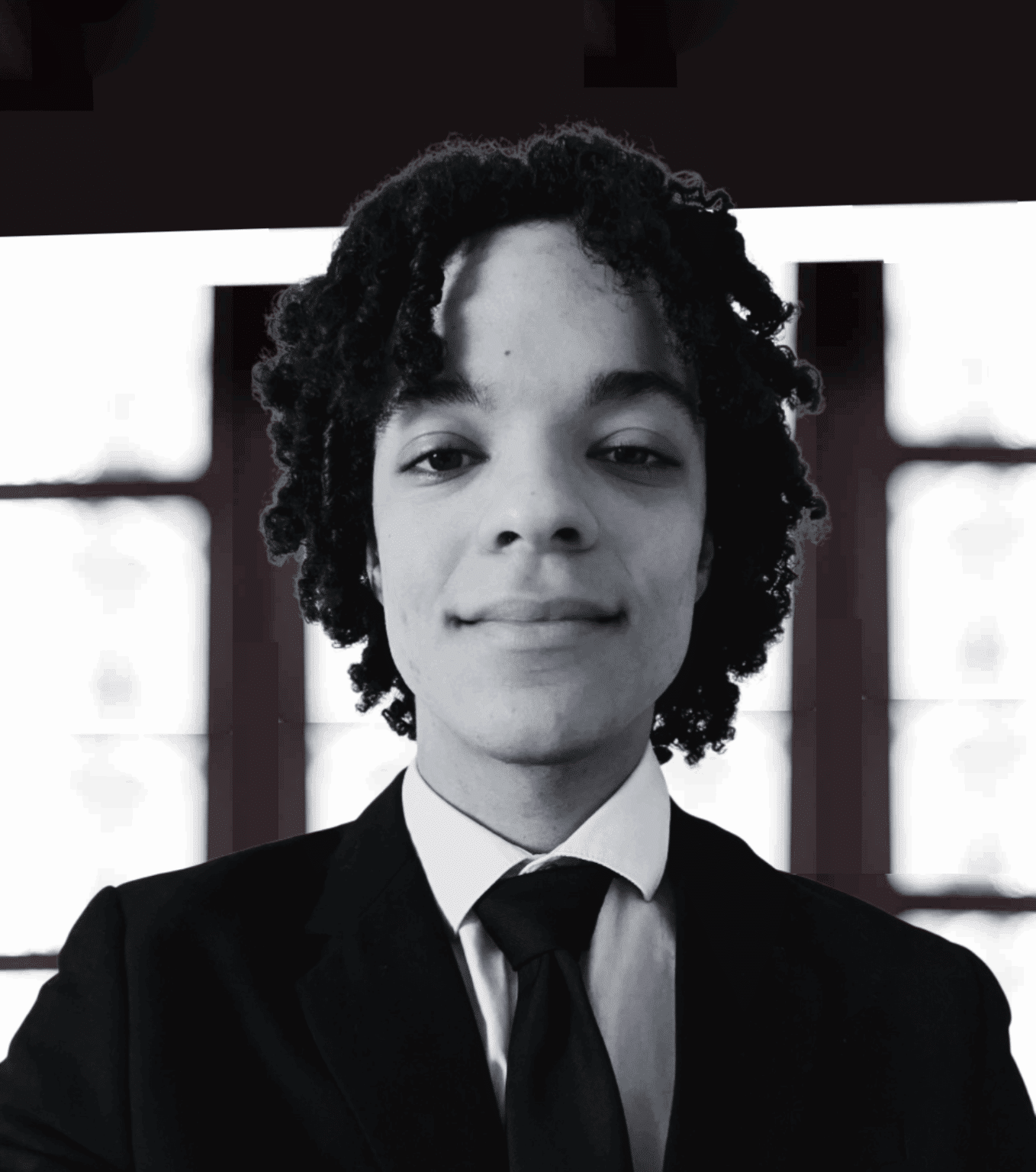

Hervé JOUANJEAN

Vice-president of Confrontations Europe

Some Member States have responded to the massive influx of migrants by temporarily reintroducing controls at their borders, as per the emergency procedures provided for in the Schengen Borders Code. Consequently, some people are claiming that the Schengen Area has failed, which is an easy but ineffective position to take. Schengen is suffering from a lack of trust between the participating Member States. But Schengen must be endowed with more efficient control procedures.

Over 1.5 million irregular migrants crossed the external borders of the European Union in the first 11 months of 2015 (1). That is almost twice as many irregular migrant crossings than in the period 2009-2014. This massive influx has put considerable strain on the mechanisms introduced under the Schengen agreement, which is now an integral part of the Community acquis. It has brought their weaknesses to light, especially since – for obvious geographic reasons – the initial pressure has fallen primarily on southern European countries like Greece, some of which are in a fragile economic state.

Several Member States (including France) have taken urgent and exceptional measures in accordance with the Schengen Borders Code, leading some observers to claim that the Schengen Area is dead. That is not only too hasty, but it is also rather irresponsible. In this context, it is worth remembering what President Juncker said to the European Parliament last November: “A single currency doesn’t make sense if Schengen fails. It is one of the main pillars of European construction.” Those who regularly drive from Paris to Brussels can testify to that – how can the single market survive with wagons queuing for five miles at the French border? We have never seen anything like it, even before the single market. It is no coincidence that the Schengen signatories stated in the recitals to the agreement that they were “prompted by the resolve to achieve the abolition of checks at their common borders on the movement of nationals of the Member States of the European Communities and to facilitate the movement of goods and services.” The Schengen agreement is part of the economic model upon which the European Union is built. At a time when increasing the competitiveness of Europe’s economy is a priority, it would be suicidal to reintroduce national borders.

Distrusts between Member states

That said, there cannot be a Schengen Area without internal borders if Europe’s external borders are not efficiently controlled and protected, and there is no doubt that it is in serious trouble. One could draw a parallel between the incompletion of the Eurozone brought to light by the 2008 crisis and the Greek crisis, and the incompletion of the Schengen Area revealed by the migrant crisis. We know what the problems are this time around too. The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union is clear and ambitious. It describes in detail the controls to which persons crossing the EU’s external borders are subject, the conditions governing their movement and the establishment of an integrated external border management system. It also discusses the common asylum policy. However, the practice does not match the theory because the Member States are unwilling to trust each other; there is a lack of solidarity within the Schengen Area and individual countries are reticent to share some aspects of their national sovereignty.

It is difficult to stem a huge tide of migrants. Remember the flood of Spanish refugees at the French border during the Spanish civil war, and the long lines of Belgian and French refugees during the 1940 collapse. But the influx can be controlled. We have the means. The rules on border controls specify that irregular migrants must be registered and then directed either towards the asylum procedure or the return procedure. The fingerprinting requirement was not properly implemented for a long time, but with the establishment of hotspots the situation has improved a lot. Eighty percent of migrants are now fingerprinted thanks to the European budget, which is going to finance the latest equipment needed for the Eurodac system.

Frontex short of staff

However, 60% of return decisions are not enforced because many third states refuse to readmit their citizens and because readmission agreements are complex and difficult to implement. With or without Schengen, the problem will not go away. The migrants become illegal and, in general, continue their journey to their chosen destination. The Commission has initiated numerous procedures against Member States who do not adhere to European rules, to little effect so far. Asylum seekers also carry on towards their preferred Member State even though, according to the Dublin regulation, it is the country of entry that is responsible for examining their application. The Frontex agency, tasked with promoting, coordinating and developing external border controls, is desperately short of staff, equipment and money, despite repeated appeals from the Commission. Databases like the Schengen Information System (SIS), which is the backbone of Schengen cooperation, are subject to numerous restrictions, limiting access to national data that could be useful to other Member States.

Complex readmission agreements

Would the situation improve if the Member States were to regain full control of their national borders? Given the situation in Great Britain, an insular state that is not a member of the Schengen Area, it is doubtful. The problem can only be resolved at EU level. The migrant crisis and the terrorist attacks and threats in France and other EU countries call for action and cooperation.

Relocation plan

The Schengen evaluation mechanism was established in 2013 to create a climate of trust, by verifying that each Member State has fulfilled the technical and legal preconditions for implementing the Schengen acquis. A relocation plan has been adopted to help Member States on the front line of the crisis, despite initial reticence on the part of some.

In December, the European Commission proposed a highly ambitious action plan with the aim of introducing a whole wealth of means to strengthen external border controls. The goal is to establish a European border and coast guard to ensure European border control standards are enforced and it will provide greater operational support to Member States where necessary. Frontex will play a much bigger role in risk prevention and control, and in managing the return of illegal migrants to their home countries. The Schengen Borders Code will be amended to allow for systematic document verification at the European Union’s external borders.

Some Member States have reservations about certain aspects of the Commission’s proposals. For example, there has been a great deal of discussion about the relocation plan. But let’s be clear about this. European solidarity is not an à la carte menu. We can’t extol its virtues when it comes to the European budget and then reject it when we are asked to take in political asylum seekers. Hopefully, this will not be a sticking point in future discussions. That would be a shame, at what is such a landmark moment for the European Union.

Html code here! Replace this with any non empty text and that's it.